Skin Immune System Function: Innate and Adaptive Immunity

20th Nov 2025

Your skin does more than keep water in and germs out. It runs its own defense network that recognizes threats, launches attacks, and remembers past invaders. This system includes specialized cells that patrol your skin layers, proteins that tag intruders for destruction, and chemical signals that coordinate responses to infection or injury. When it works properly, you barely notice it fighting off bacteria, viruses, and fungi every day.

Your skin does more than keep water in and germs out. It runs its own defense network that recognizes threats, launches attacks, and remembers past invaders. This system includes specialized cells that patrol your skin layers, proteins that tag intruders for destruction, and chemical signals that coordinate responses to infection or injury. When it works properly, you barely notice it fighting off bacteria, viruses, and fungi every day.

This article breaks down how your skin immune system operates from the cellular level up. You'll learn about the key cells and layers involved, how innate and adaptive responses differ but work together, and what happens when this defense network malfunctions. We'll also cover practical ways to support your skin's natural immunity, particularly when dealing with stubborn infections that challenge its protective capabilities. Understanding these mechanisms helps you make informed decisions about treating skin conditions and supporting your body's built-in defenses.

Why the skin immune system matters

Your skin immune system function determines whether a minor scratch heals cleanly or develops into a persistent infection. Every day, your skin encounters thousands of bacteria, viruses, and fungi that could potentially cause harm. Without this defensive network, even simple activities like touching a doorknob or playing in the park would expose you to serious health risks. The skin immune system acts as your first responder, identifying threats before they penetrate deeper tissues or enter your bloodstream.

Disruptions to this system create real consequences. Children with weakened skin immunity often develop conditions like molluscum contagiosum, where the virus spreads across multiple body areas because the skin cannot mount an effective defense. Adults may experience recurring folliculitis or persistent acne when their skin's immune response becomes imbalanced. These conditions cause physical discomfort, visible lesions, and often social anxiety, particularly in children who face teasing from classmates.

The skin immune system doesn't just fight infections. It also regulates healing, prevents excessive inflammation, and maintains the delicate balance between protection and overreaction.

Understanding how your skin's defense mechanisms work helps you recognize when something goes wrong. You can identify warning signs earlier, choose appropriate treatments, and take preventive measures that support natural immunity. For parents dealing with their child's skin infection or adults managing chronic conditions, this knowledge transforms frustration into informed action.

How to support your skin immune system

Your skin immune system function improves when you provide the right building blocks and avoid practices that compromise its effectiveness. You cannot directly control how immune cells patrol your epidermis, but you can create conditions that help them operate at peak efficiency. Most people unknowingly undermine their skin's defenses through daily habits they assume are harmless.

Prioritize nutrition and hydration

Your immune cells require specific nutrients to manufacture antimicrobial peptides and coordinate inflammatory responses. Vitamin D supports the production of cathelicidins, proteins that punch holes in bacterial membranes. You get vitamin D through sunlight exposure or fortified foods, though many people remain deficient without realizing it. Zinc and vitamin C also contribute to skin barrier integrity and immune cell function. When you eat processed foods high in sugar and low in nutrients, you deprive your skin of raw materials it needs for repair and defense.

Water intake directly affects your skin's ability to maintain its protective barrier. Dehydrated skin develops microscopic cracks that allow pathogens easier entry. You should drink water based on your activity level and climate rather than following arbitrary eight-glasses rules.

Avoid overwashing and harsh products

Excessive washing strips away beneficial bacteria that compete with harmful pathogens for space on your skin. These microorganisms form part of your first line of defense, yet antibacterial soaps marketed as protective actually disrupt this microbial balance. You only need gentle cleansers for most body areas, applied once or twice daily. Hot water and aggressive scrubbing also damage the lipid barrier that prevents moisture loss and pathogen entry.

Your skin immune system functions best when you maintain its natural pH and avoid disrupting the microbiome that supports immune responses.

Products containing alcohol, fragrances, or harsh chemicals can trigger inflammation that weakens immune function. Children with sensitive skin particularly suffer from these irritants, developing conditions that their immune system struggles to resolve.

Address infections promptly

When you notice unusual bumps, redness, or persistent irritation, you give your immune system the best chance by acting quickly. Infections like molluscum contagiosum spread more easily when left untreated, overwhelming localized defenses. Supporting your skin during active infections requires targeted treatments that work with, rather than against, your body's natural responses.

Key cells and layers in skin immunity

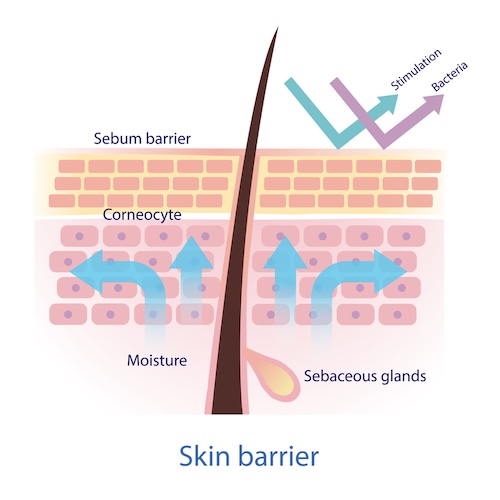

Your skin immune system function depends on a coordinated network of cells distributed across two main layers: the epidermis and the dermis. Each layer houses specific immune cells with distinct roles, creating overlapping zones of protection that catch threats at different depths. Understanding these components helps you appreciate why some skin infections affect only the surface while others penetrate deeper, requiring different treatment approaches.

The epidermis defense line

Your epidermis contains keratinocytes, which make up roughly 90% of the cells in your skin's outer layer. These cells do more than form a physical barrier. They detect invaders through pattern-recognition receptors that identify molecular signatures unique to bacteria, viruses, and fungi. When keratinocytes encounter these patterns, they release antimicrobial peptides that directly destroy pathogens and signal other immune cells to join the fight.

Langerhans cells patrol your epidermis like security guards scanning a building. These dendritic cells extend arm-like projections into the stratum corneum, your skin's outermost layer, where they capture foreign particles. After grabbing an invader, Langerhans cells travel to nearby lymph nodes to present what they found to T cells, initiating a targeted immune response. You have roughly 1,000 Langerhans cells per square millimeter of skin.

The dermis patrol network

Below your epidermis, the dermis contains blood vessels and lymphatic channels that allow immune cells to move between your skin and the rest of your body. This layer hosts dermal dendritic cells, macrophages, and mast cells that respond to deeper infections or tissue damage. Macrophages engulf pathogens through phagocytosis, essentially eating invaders and destroying them internally. They also release cytokines, chemical signals that recruit additional immune cells to infection sites.

Your dermis functions as both a battlefield and a communication hub, where immune cells receive reinforcements through blood flow and coordinate responses to threats that breach the epidermis.

Mast cells in your dermis store pre-made inflammatory chemicals in granules. When these cells detect allergens or injury, they release histamine and other mediators that increase blood vessel permeability, allowing more immune cells to reach the problem area. This response causes the redness and swelling you notice around infected bumps.

Key immune cell interactions

T cells and B cells circulate through your dermis, scanning for antigens presented by dendritic cells. These lymphocytes create immunological memory, explaining why your body fights some infections more effectively after prior exposure. Natural killer (NK) cells patrol your skin looking for virally infected cells or cancerous cells, destroying them before they spread. This multilayered cellular network ensures that your skin immune system function addresses threats through multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

Innate and adaptive responses in the skin

Your skin immune system function operates through two distinct but interconnected defense strategies. Innate immunity responds immediately to any breach or threat, using preprogrammed recognition patterns that activate within minutes. Adaptive immunity takes longer to mobilize but delivers precision strikes against specific pathogens, creating lasting memory that protects you from future encounters. These systems work simultaneously, with innate responses buying time for adaptive mechanisms to gather intelligence and mount targeted attacks.

Innate immunity works immediately

When bacteria penetrate your skin barrier through a cut or scratch, your innate immune system responds before you finish washing the wound. Keratinocytes release antimicrobial peptides like defensins and cathelicidins that directly kill common pathogens by disrupting their cell membranes. These peptides act within minutes, providing immediate protection while your body mobilizes additional defenses.

Toll-like receptors on keratinocytes and immune cells detect molecular patterns unique to pathogens. These receptors recognize bacterial cell walls, viral genetic material, and fungal components, triggering inflammation that brings more immune cells to the site. Your skin releases cytokines and chemokines, chemical signals that recruit neutrophils from your bloodstream. Neutrophils arrive within hours, engulfing bacteria and releasing toxic substances that destroy invaders.

Your innate immune response operates on pattern recognition rather than specific identification, attacking anything that displays microbial signatures your body evolved to recognize as dangerous.

Macrophages patrol your dermis continuously, consuming dead cells and pathogens through phagocytosis. Natural killer cells scan for virally infected cells, destroying them before viruses replicate and spread. This rapid response system handles most minor threats automatically, explaining why small cuts heal without infection.

Adaptive immunity builds targeted defenses

Your adaptive immune system creates customized weapons against specific invaders that survive the innate response. Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells capture pathogen samples and travel to lymph nodes, where they present these antigens to naive T cells. This process takes several days, during which your T cells learn to recognize that particular pathogen.

CD4+ helper T cells coordinate the immune response by releasing cytokines that activate other immune cells. They determine whether your body needs antibody production, enhanced cell-killing activity, or specialized responses against parasites. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directly attack cells infected by viruses or displaying abnormal proteins, preventing the spread of intracellular pathogens. B cells produce antibodies specific to the invader, proteins that bind to pathogens and mark them for destruction by other immune cells.

Memory cells remain in your skin and circulation after infection resolves. These cells allow your adaptive immunity to respond faster and stronger during subsequent exposures to the same pathogen, often preventing reinfection entirely.

How both systems coordinate

Innate immunity shapes adaptive responses through the cytokines and signals it releases. Dendritic cells activated by innate pattern recognition determine which type of T cell response develops. For bacterial infections, your innate system promotes Th1 responses that enhance macrophage killing. For parasitic infections, it favors Th2 responses that activate eosinophils and antibody production.

This coordination explains why some skin infections resolve quickly while others persist. Viruses like molluscum contagiosum evade both systems by suppressing inflammatory signals and hiding from adaptive recognition, requiring targeted treatment to support your body's natural defenses.

When the skin immune system goes wrong

Your skin immune system function can malfunction in three primary ways: attacking your own tissues, failing to recognize real threats, or overreacting to harmless substances. These disruptions create conditions that range from mildly annoying to severely debilitating, affecting both physical health and quality of life. Understanding these malfunctions helps you recognize warning signs and seek appropriate treatment before problems escalate.

Autoimmune attacks on your own skin

Your immune system sometimes mistakes your skin cells for foreign invaders, launching attacks against healthy tissue. Psoriasis develops when T cells trigger excessive keratinocyte production, creating thick, scaly patches that itch and crack. Your body accelerates skin cell turnover from the normal 28-day cycle to just 3-4 days, causing cells to pile up on your skin's surface. Lupus causes your immune system to attack skin cells directly, creating butterfly-shaped rashes across your face and sensitivity to sunlight.

Autoimmune skin conditions occur when the regulatory mechanisms that normally prevent self-attack fail, allowing your immune cells to target proteins they should recognize as part of your own body.

These conditions often fluctuate in severity, with stress, infections, or environmental triggers causing flare-ups that worsen symptoms.

Weakened defenses allow persistent infections

Some individuals have compromised skin immunity that cannot effectively fight common pathogens. Children frequently develop molluscum contagiosum when their developing immune systems fail to clear the virus efficiently, allowing lesions to spread across multiple body areas. Adults with conditions like diabetes experience impaired neutrophil function, making minor cuts vulnerable to bacterial infections that heal slowly or develop into abscesses.

Primary immunodeficiency disorders prevent your skin from mounting adequate responses, while medications like corticosteroids suppress immune activity to manage other conditions but leave you vulnerable to opportunistic infections.

Overactive responses create unnecessary inflammation

Your immune system sometimes reacts aggressively to harmless substances, producing allergic contact dermatitis when you touch certain metals, fragrances, or plants. Mast cells release excessive histamine, causing hives, swelling, and intense itching that disrupts daily activities. Atopic dermatitis develops when your skin barrier weakens and your immune system overreacts to environmental triggers, creating chronic inflammation that damages healthy tissue while attempting to fight perceived threats.

Putting it all together

Your skin immune system function relies on coordinated efforts between innate and adaptive responses, with specialized cells working across multiple layers to protect you from infection. Understanding this system helps you recognize when something goes wrong, whether your body overreacts to harmless substances or fails to clear persistent infections. The knowledge you gained here transforms abstract concepts into practical awareness of how your body defends itself and when it needs support.

Supporting your skin's natural defenses through proper nutrition, gentle cleansing practices, and prompt attention to infections gives your immune cells the best conditions to operate effectively. When dealing with stubborn skin infections like molluscum contagiosum that challenge your immune system, targeted treatments can work alongside your body's defenses to resolve the condition. Mollenol products support your skin's natural immunity while addressing infections that overwhelm standard immune responses, helping restore the balance your skin needs to protect and heal itself.